Paul Gessing’s Testimony on the economic impacts of Medicaid expansion: Before the Health and Human Services Committee New Mexico Legislature, Santa Fe

Good morning Sen. Ortiz y Pino, Rep. Espinoza, and members of the committee. I am Paul Gessing, president of the Rio Grande Foundation, an independent, nonpartisan, tax-exempt research and educational organization dedicated to promoting prosperity for New Mexico.

I appreciate this opportunity to provide my organization’s perspective on whether the benefits of Medicaid expansion in New Mexico outweigh the costs and whether a “multiplier effect” exists by which increased federal dollars will generate increased economic growth in our state.

Introduction

Before discussing the economic and multiplier impacts of Medicaid expansion, I feel it is important to discuss the impact of Medicaid on actual health care outcomes. Supporters of free markets and skeptics of the efficacy of government programs are are often accused of being callous or uncaring to the poor, but we actually want government spending to be used in ways that have proven, positive results.

There is no question that Medicaid expansion is a massive expansion of a health care entitlement. According to Congressional Budget Office, between 2014 and 2022, expanding Medicaid will cost American taxpayers at the combined federal and state levels $1 trillion. Before discussing the economic impact on New Mexico, it is important to ask what kind of health care we getting for that money.

For starters, the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services found that over half of providers no longer accept Medicaid patients. Of doctors who do accept Medicaid, the provider networks are narrow and nearly one-third face wait times of over a month.

Last year, The Wall Street Journal profiled Farmington family physician Holly Abernethy, who

has turned away all newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries because she can’t sustain her practice expenses if her proportion of Medicaid patients grows much beyond her current 13%.

For a moderately complex office visit, she is paid about the same as [a] nurse practitioner: about $80 from Medicaid and about $160 on average from commercial insurance.

Says Dr. Abernethy, “I would love to see every Medicaid patient that comes through my door.” “If you give people coverage, they should be able to utilize it.” But making it work would extend her workday, and “I have three small children and I miss them.”

Moving from anecdotal to empirical evidence, it is worth considering Oregon’s experience. In 2008, a total of 29,835 Oregonians were given the opportunity to apply for the state’s Medicaid program out of almost 90,000 people on the waitlist. About 30 percent of those who were selected from the waitlist both chose to apply for Medicaid and met the eligibility criteria. Because it examined a unique, real-world experiment complete with a randomly selected control group, the study of Oregon’s Medicaid expansion is considered the “gold standard” in health-care research.

The study’s results have been published in academic journals, including The New England Journal of Medicine and the The American Economic Review in 2013. Its conclusion was that “Medicaid increased health care utilization, reduced financial strain, and reduced depression, but produced no statistically significant effects on physical health or labor market outcomes.”

The Oregon study is not alone in casting a skeptical light on Medicaid’s health benefits:

• A 2010 study of 1,231 patients with cancer of the throat, published in the medical journal Cancer, found that Medicaid patients and people lacking any health insurance were both 50 percent more likely to die when compared with privately insured patients—even after adjusting for factors that influence cancer outcomes. Medicaid patients were 80 percent more likely than those with private insurance to have tumors that spread to at least one lymph node.

• A 2010 study of 893,658 major surgical operations performed between 2003 to 2007 published in the Annals of Surgery found that being on Medicaid was associated with the longest length of stay, the most total hospital costs, and the highest risk of death. Medicaid patients were almost twice as likely to die in the hospital than those with private insurance. By comparison, uninsured patients were about 25 percent less likely than those with Medicaid to have an “in-hospital death.”

• A 2011 study of 13,573 patients, published in the American Journal of Cardiology, found that people with Medicaid who underwent coronary angioplasty (a procedure to open clogged heart arteries) were 59 percent more likely to have “major adverse cardiac events,” such as strokes and heart attacks, compared with privately insured patients. Medicaid patients were also more than twice as likely to have a major, subsequent heart attack after angioplasty as were patients who didn’t have any health insurance at all.

• A 2011 study of 11,385 patients undergoing lung transplants for pulmonary diseases, published in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, found that Medicaid patients were 8.1 percent less likely to survive 10 years after the surgery than their privately insured and uninsured counterparts. Medicaid insurance status was a significant, independent predictor of death after three years—even after controlling for other clinical factors that could increase someone’s risk of poor outcomes.

In all of these studies, the researchers controlled for the socioeconomic and cultural factors that can negatively influence the health of poorer patients on Medicaid.

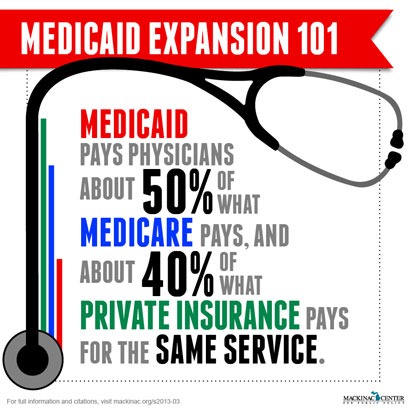

So why do Medicaid patients fare so badly? Payments to providers have been reduced to literally pennies on each dollar of customary charges because of sequential rounds of indiscriminate rate cuts. As a result, doctors often cap how many Medicaid patients they’ll see in their practices. Meanwhile, patients can’t get timely access to routine and specialized medical care.

All that being said about the most important issue, the impact of Medicaid on health outcomes, I am primarily here to discuss the financial impact of Medicaid expansion on New Mexico’s economy and state budget.

In the current fiscal year, New Mexico will spend more than $5.5 billion on Medicaid, with state revenue covering just under $900 million of the total. By 2017, fully a third of the state’s population will be on Medicaid. At a time when revenue is dropping from the decline of the oil-and-gas sector, the program is seriously jeopardizing the state’s ability to balance its budget. By 2020, it is estimated that the state’s bill for covering newly eligible Medicaid recipients will be $163 million.

A Flawed Theory

The “multiplier effect” is the theory that government spending stimulates jobs creation and income growth. Many proponents of Medicaid expansion claim that since it is largely funded with “free” money from Washington, it is an economic-development tool. But, as Harvard economist Robert Barro explained in a September 2009 National Bureau of Economic Research paper, “it is wrong … to think that added government spending is free.” The money Washington is sending to New Mexico for Medicaid must come from either taxes or borrowing.

The national debt is currently $18.6 trillion. At least in the short term, the burden is sure to grow. Unfunded liabilities for Social Security and Medicare are estimated to be in the hundreds of trillions of dollars. This level of debt-creation will not continue. New Mexico, a state uniquely dependent on Washington appropriations, cannot count on an endless spigot of federal cash, for Medicaid or any other program. A reckoning is coming. It is likely to be very ugly for taxpayers in the Land of Enchantment.

The ‘Medicaid Multiplier’ Exposed

On the issue of the multiplier itself, after conducting a survey of the economic literature, Valerie Ramey, an economist at the University of California, San Diego concluded: “For the most part, it appears that a rise in government spending does not stimulate private spending; most estimates suggest that it significantly lowers private spending.” Studies by many others, including economists at the International Monetary fund, concur with Ramey’s finding.

In an effort to better understand the alleged “multiplier effect,” the Rio Grande Foundation recently examined economic performance in the 24 states that expanded Medicaid in January 2014, comparing it with the 20 states that did not. Despite tens of billions of “free” money flowing into expansion states with no state match required until 2017, the percentage of job growth in the two groups was essentially the same, with a slight edge to the non-expanding states:

The absence of a Medicaid “multiplier” is particularly stark in New Mexico. Residents continue to leave our state, the labor participation rate is falling, and unemployment is rising. Our state has yet to recover the number of jobs it had during its employment peak, more than seven years ago. The state’s extensive matrix of welfare programs is surely an incentive to remain on public assistance rather than seek opportunities in the job market.

There are many weaknesses in the claim that Medicaid expansion creates jobs for the workers needed to treat newly eligible beneficiaries. While employment in New Mexico’s health-services industry is rising, it is not at all clear that Medicaid expansion is causing the growth. The sector has been adding jobs for many years, and even increased its employment during the Great Recession.

Even if it were the case that Medicaid expansion creates healthcare jobs, in the assessment of Harvard scholars Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra,

(e)mployment in the health care sector should be neither a policy goal nor a metric of success. The key policy goals should be to achieve better health outcomes and increase overall economic productivity, so that we can all live healthier and wealthier lives. Our ability to ensure access to expensive but beneficial treatment is hampered whenever health care policy is evaluated on the basis of jobs. Treating the health care system like a (wildly inefficient) jobs program conflicts directly with the goal of ensuring that all Americans have access to care at an affordable price.

One penalty of Medicaid expansion that its proponents consistently avoid addressing is the impact it has on those with non-government coverage. Broadening the program imposes “a hidden tax on … people with private insurance. Expanding Medicaid leads hospitals and doctors to shift costs onto patients with private insurance thus making private insurance less affordable and contributing to the vicious cycle of increasing the number of people without insurance.” Prices for insurance premiums are rising—not falling, as Obamacare supporters claimed – and Medicaid expansion is a likely contributor to the cost of private coverage.

In Conclusion

Prior to the enactment of this new health care law, Medicaid provided New Mexico with 70 cents on the dollar with little evidence that it “stimulated” New Mexico’s economy.

Perhaps the worst aspect of Medicaid expansion is that, like so many federal programs, it relied on the promise of “free money” to the states. If any welfare program is worth enacting or expanding, it should be the taxpayers of New Mexico that support paying into a program for the benefit of their friends and neighbors. After all, we all do want better health care outcomes.

A cash-grab based on long-discredited Keynesian “stimulus” theory with little or no health benefits isn’t just unwise, it’s immoral. Think of what else we could do with $1 trillion.

In the short term, New Mexico should work with other states to press the federal government for the flexibility required to fix a badly broken and irresponsibly unsustainable program.

Medicaid desperately needs a sweeping overhaul. Reforms must be consumer-oriented, permitting beneficiaries to obtain private coverage in a competitive marketplace. Time limits similar to those imposed under the creation of the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program in the 1990s, are also worth consideration.

In the long term, aggressive implementation of proven economic-development strategies will create the prosperity that will enable New Mexicans to obtain private insurance, either through their employers or purchased individually. The way to gauge successful healthcare policy in New Mexico is to track how many people are leaving, not joining, our population of Medicaid enrollees.

Thank you for your time today.