Economy

post

Mandated Minimum Wage Ships Jobs Outside City Limits

When Albuquerque voters go to the polls Oct. 4, they’ll be deciding an issue with far-reaching consequences. The question is whether Albuquerque businesses will be required to pay a minimum wage of $7.50 an hour, to rise annually with inflation. Currently there’s a nationwide minimum wage of $5.15.

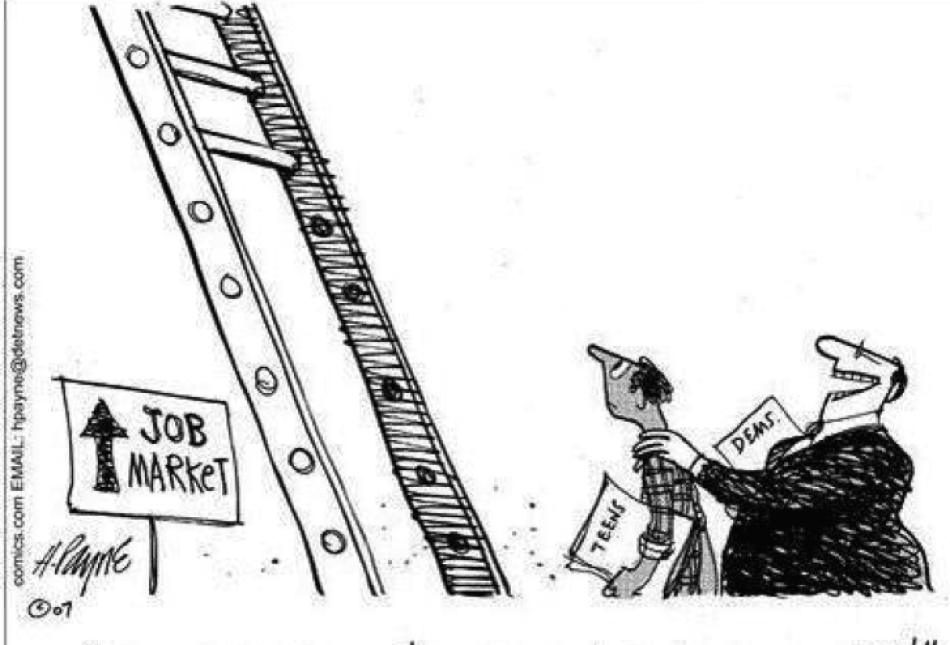

Nearly all economists, supported by empirical studies, agree that the net effects of minimum wages are harmful. Put plainly, workers who aren’t worth $7.50 an hour to their employers would lose their jobs. Entry-level workers with little experience would have an even harder time climbing the first step of the career ladder. Few would realize that it was the minimum wage that kept them from landing a job.

Low-paying jobs are often a gateway into the world of work for unskilled persons who lack experience. Most minimum-wage earners move up to better paying jobs. By accepting a low-paying job, an entry-level worker is paying for on-the-job training.

Whatever negative effects a nationwide minimum wage may have, a local minimum wage – one that applies only to Albuquerque in isolation – would be far more harmful to local business and unskilled workers.

As with a national minimum, firms have the option of dismissing workers who aren’t worth the mandated minimum. But with an Albuquerque-only minimum, employers have the additional option of evasive action – moving across the city border.

Any manufacturing firm would consider relocating. Many businesses that need to be close to their customers might decide to stay put and raise prices (or go out of business) but some would move. Indeed, the measure being voted on should be called “The Full Employment for Rio Rancho Act of 2005.”

The burden of a higher minimum wage could be quite significant. Consider an Albuquerque fitness club that employs 100 workers, of which 50 earn an average of $6 an hour. Raising them by $1.50 for 2,000 hours a year would cost $3,000 each, or $150,000 total. In addition, workers already making $7.50 would get some sort of raise, and then there is Social Security and possibly other benefits, bringing the total cost to at least a quarter of a million dollars. Clearly this is serious money, and might eat up all the firm’s profits.

To soften the blow, the club might replace its 50 low-paid workers with 40 more skilled workers, so clearly the unskilled workers would suffer the most. Also, the club’s survival would probably require an increase in prices for its members. A lose-lose game!

A minimum wage would create a bureaucratic snarl for the city and for business alike. For city government, it would be new tasks of certification, monitoring, enforcement and dispute resolution. This would require a new bureau – not cheap – empowered to snoop into companies’ records. The current controversy over the proposed minimum wage suggests that “dispute resolution” would be a major task.

Business would be on the receiving end of much of the paperwork burden related to the ongoing task of proving their compliance. In addition, the provision that would allow anyone to have access to certain nonwork areas “to inform employees of their rights” is a wild card, probably causing extensive friction as various groups intrude on business property.

The business climate – that amorphous but vital key to local prosperity – is also at stake. In the past, state and local governments, plus the business community, have tried hard to demonstrate that Albuquerque is friendly to business. Obviously a $7.50 minimum wage would send a bad signal to out-of-state firms considering moving here, depending on their wage structure.

But more important would be the not-so-subtle message that Albuquerque municipal government stands ready to insert itself into private working arrangements between companies and their employees. What’s next, they would wonder. Albuquerque would never again make one of those “Best Of” lists produced by Forbes magazine and others.

The logic of a mandatory minimum wage is flawed. Basically, it is the philosophy that a government can force producers to pay employees more than the value of their contribution to production.

If we really want to raise the wages of unskilled workers we should induce them to become more productive by acquiring more schooling and better skills — either on the job or at school. A nation, let alone a city, cannot alleviate poverty by imposing a mandatory minimum wage. It’s like telling water to flow uphill.

So Albuquerque voters face a rare opportunity: the chance to reject an intrusive regulation that both fails in its purpose and creates extensive mischief.

Kenneth M. Brown is research director of the Rio Grande Foundation. Micha Gisser is professor emeritus of economics at the University of New Mexico and a senior fellow at the foundation.