A secretary of state power grab on nonprofit privacy

The following appeared in the Santa Fe New Mexican on July 12, 2017.

We all know how a bill becomes a law, right? A lawmaker writes a bill, the Legislature passes it, and then the governor signs it. At least, that’s what the New Mexico Constitution says. Unfortunately, losers in the legislative process are increasingly willing to ignore that process, and a rule-making currently underway in Santa Fe shows how.

This spring, the New Mexico Legislature considered imposing new donor disclosure rules on nonprofit organizations. The measure was vetoed by Gov. Susana Martinez over privacy concerns. Now Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver is attempting to impose those rules by bureaucratic fiat, using a regulation to enact what couldn’t be done through the normal lawmaking process.

Bureaucratic rule-makings can serve an important function. They help to implement and clarify laws that are passed by the Legislature. But here, instead of implementing the law, the Secretary of State’s Office is enacting rules that were rejected in the constitutional lawmaking process. Although pitched as “political disclosure,” as Martinez wrote in her veto message in April, “the broad language in the bill could lead to unintended consequences that would force groups like charities to disclose the names and addresses of their contributors in certain circumstances.”

Furthermore, the rules, if adopted, will almost certainly be challenged in court. It wouldn’t be the first time New Mexico got itself in hot water by adopting “broad language” to try to “improve” political transparency. In New Mexico Youth Organized, et al v. Herrera, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals held that New Mexico’s definition of “political committee” was unconstitutional. The case concerned two progressive nonprofits that had spent a small portion of their budgets criticizing candidates for ties to health insurance interests.

Nevertheless, the Secretary of State’s Office now wishes to regulate this type of private activity. Forcing nonprofits to comply with rules akin to those for political committees conflicts with the 10th Circuit’s clear guidance that political action committees may “only encompass organizations that are under the control of a candidate or the major purpose of which is the nomination or election of a candidate.” If the defeated bill is enacted as a regulation, citizens will likely see their tax dollars spent defending a rule already rejected in the legislative process.

Even if the state were to prevail in court this time around, these nonprofit disclosure rules would not improve politics in New Mexico. If every citizen group that speaks about candidates’ policy positions and voting records has to behave like a PAC, pretty soon only PACs will have a voice in elections. Grass-roots and volunteer-run groups like New Mexico Youth Organized won’t be able to afford the attorneys necessary to comply with complex reporting rules. How does that help the average New Mexican voter?

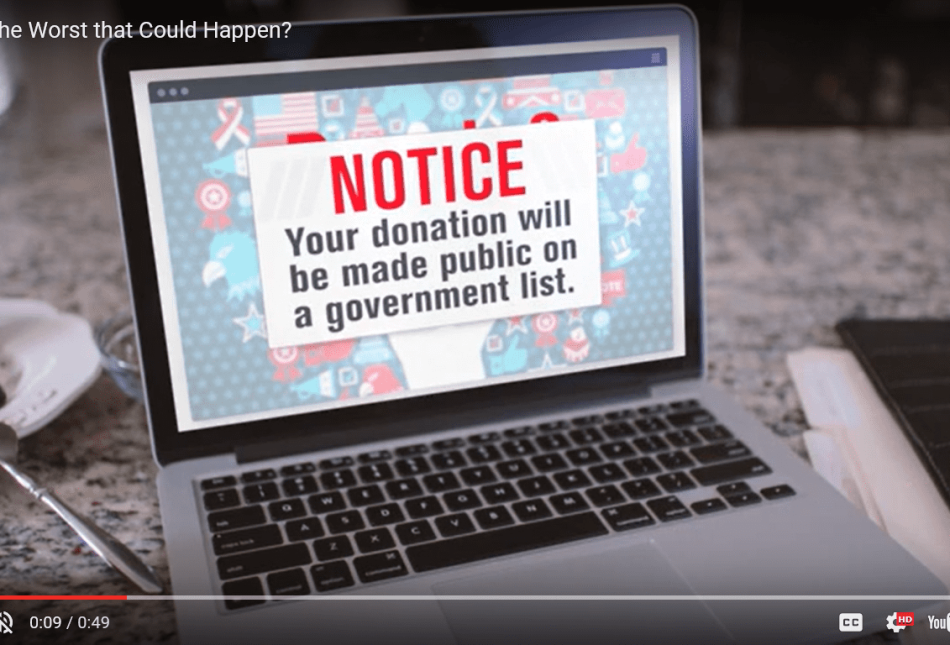

Nonprofit speech about candidates allows voters to hear the varied perspectives of groups that do valuable work in our communities. For a variety of religious, civic and political reasons, many donors to these organizations do not want to have their names and home addresses published online for their boss and nosy neighbors to see. Rest assured, many groups will choose silence over exposing their supporters’ private information.

Political transparency and personal privacy don’t have to contradict. Political committees can be made to disclose their donors without inhibiting everyone else from speaking. Donors who earmark their nonprofit gifts for campaign-related speech can be reported to the government without violating everyone else’s privacy.

The secretary of state’s proposed rules, however, would sweep up charities and their supporters as well. This isn’t just political speech. Just mention a candidate by name near any election and you’re at risk under the secretary’s proposed regulation. Martinez wisely chose to avoid this course of action for New Mexico. We should be cautious when considering proposals that restrict or chill charitable giving. We should especially not impose such policies through a subversion of the democratic process.

If this matter were appropriate to be handled by the secretary of state, it would never have been submitted to the Legislature and governor. The secretary’s proposed rules are both bad in substance and an abuse of her rule-making authority.

Bradley A. Smith, who served on the Federal Election Commission from 2000 to 2005, is chairman and founder of the Center for Competitive Politics, the nation’s largest organization dedicated solely to protecting First Amendment political rights. Paul Gessing is president of the Rio Grande Foundation, an independent, nonpartisan, tax-exempt research and educational organization dedicated to promoting liberty, opportunity and prosperity for New Mexico.